- Home

Page 4

Page 4

A Little Girl in Old Washington

A Little Girl in Old Washington Kathie's Soldiers

Kathie's Soldiers The Radio Detectives Under the Sea

The Radio Detectives Under the Sea A Little Girl in Old Pittsburg

A Little Girl in Old Pittsburg A Little Girl in Old New York

A Little Girl in Old New York Washer the Raccoon

Washer the Raccoon A Little Girl of Long Ago; Or, Hannah Ann

A Little Girl of Long Ago; Or, Hannah Ann Wheat and Huckleberries; Or, Dr. Northmore's Daughters

Wheat and Huckleberries; Or, Dr. Northmore's Daughters With Porter in the Essex

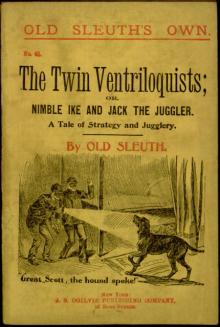

With Porter in the Essex The Twin Ventriloquists; or, Nimble Ike and Jack the Juggler

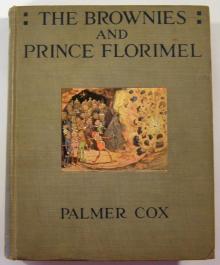

The Twin Ventriloquists; or, Nimble Ike and Jack the Juggler The Brownies and Prince Florimel; Or, Brownieland, Fairyland, and Demonland

The Brownies and Prince Florimel; Or, Brownieland, Fairyland, and Demonland A Little Girl in Old Quebec

A Little Girl in Old Quebec Helen Grant's Schooldays

Helen Grant's Schooldays The Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe; Or, There's No Place Like Home

The Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe; Or, There's No Place Like Home A Little Girl in Old St. Louis

A Little Girl in Old St. Louis Marion Berkley: A Story for Girls

Marion Berkley: A Story for Girls